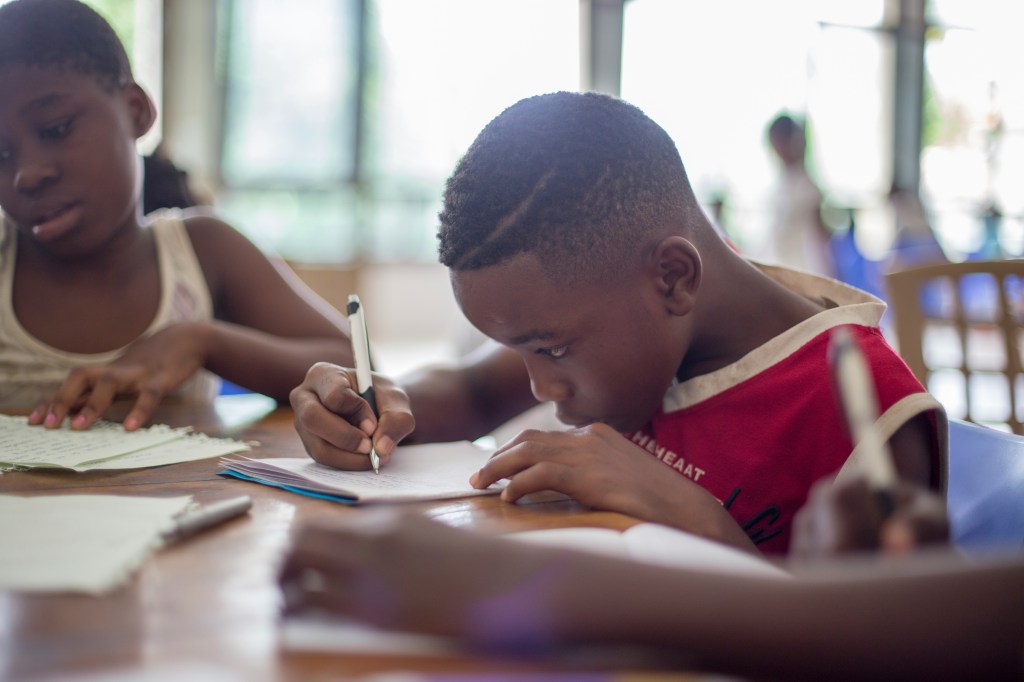

When Kaci was 8 years old, her mother, Antonia “Toni” Smith, learned about Kaci’s habits in her second grade class. Kaci is a quiet, very soft-spoken girl who likes to stare out of windows. However, because of her age, Smith didn’t think anything of it because she fell in line with her two younger siblings who were all hitting their milestones of growth together.

It wasn’t until Kaci’s second grade teacher from Charles County Schools in Maryland called a parent-teacher conference to talk about Kaci’s habits. The teacher suggested that Kaci be held back for another year in second grade and Smith said she remembers the reason was due to “misbehavior.” It is a moment she remembers with a scoff.

“A child staring out the window is not misbehaving to me,” Smith said. “Because in her classes, she was doing well, as far as the academics, she was getting C’s and B’s. And I thought, you know, that’s not unusual.”

Recalling the parent-teacher conference memory and her conversation with the teacher, Smith would say the interaction just didn’t make sense.

“Have you tried to kind of cue her back into class if she’s zoning out? Have you tried to get her attention?” Smith said, frustrated in her conversation with the teacher. “Like, is she not responding when you get her attention?”

Smith said the teacher explained to her that as a teacher, it was not her job to get Kaci’s attention. Getting nowhere with the teacher and having feelings of not being heard, Smith turned to the next best thing, her best friend, Google.

“I ended up typing in some of those things like ‘Zoning out, inability to concentrate, being distracted easily, quiet,’ things like that,” Smith said. “And between Google and WebMD, it said ‘ASD.’ It said, ‘Your child could be on the spectrum.’ She could be autistic and you should check it out.”

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that can impact a person’s learning and development. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the main symptoms of autism shown in children are repetitive routines, sensory sensitivity and social interaction challenges. These symptoms range from hand-clapping, rocking back and forth and making noises; wearing clothing from specific fabrics and eating certain foods based on textures; and using little or no speech to communicate with others or relying on others to interpret their sounds, body and facial expressions.

Elizabeth Morgan, interim director and assistant professor at California State University in Sacramento, said what Smith had gone through as a Black mother is not uncommon. As a parent of an autistic child herself, she understands the desire to advocate for children on the spectrum and the communication barriers parents face.

Morgan said in an article published in the British Journal of Sociology of Education in 2021 called, Narratives of single, Black mothers using cultural capital to access autism interventions in schools, the trust between Black parents and school personnel had become a barrier because of the differences in communication practices.

“Schools are very one directional when it comes to communication,” Morgan said. “But Black mothers, in particular, really need that relationship and need bi-directional communication in order to be able to understand and acquire information that can be useful for their advocacy.”

In 2014, a few weeks after the parent-teacher conference, Smith took Kaci to her primary care pediatrician for an autism evaluation. However, when she was told that Kaci’s pediatric facility did not do testing, she was directed back to the school for testing. But Smith said she was constantly told by the same teacher that Kaci could in no way be autistic, just a misbehaved child.

More weeks passed and Smith said she kept having run-ins with the same teacher to the point she questioned pulling Kaci out of the school. One solution she did find was independent autism testing for her daughter at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Maryland.

After sitting in the testing room for four hours with Kaci while doctors gave her different sets of tests, from reading short excerpts to putting square pegs in round holes, the results came in.

Smith said she felt relieved that in her efforts to get help for daughter, she knew she wasn’t crazy and that Kaci would finally get the accommodations she needed in school. Kaci was diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome; which was later removed from the diagnosis process. Years later as a freshman in high school, Kaci would be diagnosed with ASD.

In the same year as Kaci’s diagnosis, the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network found that the prevalence in ASD occurred in one in 56 children aged 8 years old. However, throughout the years, the likelihood of children having ASD has increased.

In a 2020 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, it was found that the prevalence of ASD among racial and ethnic groups, such as children in the Black community, was higher than that of white children, contrasting with historical patterns. For the first time, these changes suggest improved and fairer identification of ASD, especially among underserved groups. But with those changes in reporting, Black parents are finding themselves with a lack of resources and struggling to be heard by school officials, researchers and diagnostic practitioners to advocate for their autistic children. These struggles range from delayed treatments and accommodations for children of color who live with this condition.

A history of disorder

Based on history, Asperger’s – the diagnosis Kaci previously had – wasn’t just a diagnosis, said Wesley Wade, Neurodiversity Advisor for Autism Community Ventures PBC. He said Asperger’s was a diagnosis of racial privilege, which in turn, played a part in racial disparities.

“It was a diagnosis that upper middle class white boys got,” Wade said. “These young boys are just so intelligent that we got to put them somewhere. A lot of the hyper intelligent people that we know had Asperger’s were autistic, formerly known as Asperger’s. And so, Black people weren’t getting a diagnosis of Asperger’s because we didn’t think we’re intelligent.”

The removal of Asperger’s syndrome from the DSM in 2013 was aimed at improving the accuracy, consistency and utility of autism diagnoses. This decision reflected on a more nuanced understanding of autism as a spectrum disorder.

In recent years in the 2020 report, approximately 4 % of boys and 1 % of girls aged 8 years were estimated to have ASD, representing one in 36 children. In the report, they examined 6,245 children from the ADDM network in 11 states, including Maryland.

In the report CDC experts found that ASD was less common among white children (24.3 %) and children of mixed races (22.9 %) compared to Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander children, who had rates of 29.3 %, 31.6 % and 33.4 %, respectively.

The term “autism” and these areas were first introduced by Leo Kanner, a doctor from The John Hopkins Hospital, in his 1963 paper Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact.

One of the primary observations was the children’s profound lack of interest in social interaction, a departure from typical developmental milestones. Unlike their peers, these children did not seek out social engagement, showed limited responsiveness to others, and displayed an apparent indifference to affective contact.

Brian Boyd, interim director of the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute and William C. Friday Distinguished Professor in the School of Education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill said Kanner was credited to some degree with diagnosing the first kids with autism in the United States.

“This was in the 1940s and his sort of description of autism – a little bit still holds, in terms of children with social communication differences and sort of these kinds of repetitive behaviors,” Boyd said.

Throughout the years, Boyd said society endured a distressing era of parental accusations, attributing autism to inadequate parenting. This particularly singled out mothers as ‘refrigerator mothers’ – a term Kanner used in his earlier work, which implied that cold, distant parenting might contribute to autism.

“Before we realize that its etiology is brain based,” Boyd said. “It is a neurodevelopmental disorder. It is nothing about parenting. It is a genetic condition.”

Boyd said primarily in history, autism was perceived as a white middle-class disorder for several reasons.

“Partly because of the kids that Kanner diagnosed,” Boyd said. “Part of it is who were seeking the diagnosis. Part of it is a reflection of those CDC reports where we’re seeing higher prevalence rates amongst white kids.”

Even though Kanner was the first to identify autism, Heather Clarke, adjunct professor of special education at New York University and founder of The Learning Advocate LLC, said along with much of his research being debunked, things like painkillers and vaccines don’t cause autism. She said people are born autistic.

Differences in the diagnosis

In earlier years, white children had a 50 % higher prevalence of ASD compared to Black or Hispanic children. However, over time, this difference decreased until, in 2016 and 2018, ASD prevalence among Black and Hispanic children matched that of white children. From 2002 to 2010, experts found a clear link between autism prevalence and higher socioeconomic status, but by 2018, this connection became less consistent.

However, CDC experts discovered that disparities persist, particularly regarding intellectual disability, a condition characterized by limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, with a higher proportion of 50.8 % in Black children opposed to 31.8 % in white children with ASD being identified with it.

They also said the rise is due to a variety of reasons such as better diagnostic practices and decreased stigma.

The ongoing rise in ASD diagnoses, especially among non-white children and girls, underscores the necessity for enhanced support systems to ensure equitable access to diagnostic, treatment, and support services for all children affected by ASD. From the 2020 report, researchers discovered that this was the first ADDM Network report that showed the prevalence of ASD among girls has exceeded 1 %.

These differences in early childhood carry significant implications, as the labels assigned often act as barriers to accessing interventions and services that support school readiness.

Maria Davis-Pierre, licensed mental health counselor and founder of Autism In Black, a program that advocates for Black autistic individuals, said data from the CDC is inaccurate because the information doesn’t provide a deeper dive into training and education of the researcher and hold stereotypes.

“Cultural stereotypes in those biases play a significant role in the under diagnosis of autism in black girls and women,” Davis-Pierre said. “There is the stereotype which we have talked about, about how autism looks. When we are seeing media representation – when that comes up when we’re looking at that DSM, we are looking at and recognizing autism as a white male thing. And because we recognize it and see it as a white male diagnosis, then that leaves a lot of people out. And it really leaves Black girls and Black women out.”

As an autistic woman with autistic children, Davis-Pierre said there are gendered expectations that contribute to underdiagnosis as well that come from the DSM.

“That diagnostic criteria, again, is derived from debt data that is on white boys,” Davis-Pierre said. “And having a male centered view of autism means that we as females, are not considered because we present differently.”

She also said the reasons why data does not provide rates of girls with ASD as it should is because girls’ characteristics such as masking, a coping mechanism to navigate environments where their authentic selves may not be fully accepted or valued, is not seen in the DSM because of misdiagnosis such as eating disorders, depression and anxiety.

According to Jamie Pearson, associate professor of special education and educational equity at North Carolina State University, these notable gaps in research have history behind them.

“One of the things that we know about the diagnosis or identification of autism historically, is that Black and brown children, children of color broadly, have historically been less likely to be identified with autism and they take longer to get access to services,” Pearson said. “We also know that the educational outcomes and outcomes related to service provision are less so for Black children.”

Because of the gaps, Pearson created Fostering Advocacy, Communication, Empowerment and Support, a program based at North Carolina State University, advocating for parents to support Black families raising children and youth with autism. She said part of developing FACES is to help address some of the disparities that we see in the identification of autism and Black children in access to services.

Pearson said many Black children are still not getting the same access to services needed as their white peers. She said there are several reasons why access to services are different due to implicit and explicit bases diagnosticians might have.

“Other disparities related to race in autism is because Black children are more likely to be identified with a behavior disorder than with autism,” she said. Just as Kaci was.

Pearson said for example, a pediatric or developmental psychologist might have some implicit biases that play a role in how they view and interpret the diagnostic criteria in a white child versus a Black child, showing “a few racial and cultural challenges and barriers that create quite a few racial and cultural barriers that create challenges for Black families in particular.”

Advocacy starts with the parents

LaTisha Brown, adjunct professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill said she believes these disparities are co-occurring in female and Black populations because many research articles published on autism are not Black centered. As a Black mother to an autistic boy, Brown said the research lacks cultural aspects.

“And one of those being that many times in Black families, behavior can be received as a sign of disrespect,” Brown said. “And so we think about autistic children and just kind of managing emotional dysregulation and sensory needs. Many times, if we have a lack of awareness of what autism is and what sensory needs are – what ADHD could be, we may perceive that our child is just misbehaving and disrespecting the cultural values that have been ingrained in us for generations.”

Brown said once parents seek to disrupt that thought pattern, they become sensitive to the needs of their child and become sensitive to having a full understanding of what the diagnosis is, what it means and what their child’s needs are.

As a parent to her only Black autistic son, Maki, Stacey Hazel said Maki had issues in school that pushed her to get Maki diagnosed. She said she never saw Maki’s actions as behavioral issues school officials from the West Orange school district in New Jersey had described.

“It wasn’t behavioral to me, it was just my son,” Hazel said. “I always call him my quirky little kid because he was just different. He was really different from anybody in my family and he was really, really smart early on.”

She said in the West Orange school district, she felt that officials have resources that are not individualized for each student like her son.

“I feel like they are equipped but they’re equipped for a cookie cutter type situation, not individually based situations,” Hazel said. “I felt like they put everybody in a box and they want to give you services based on this box.”

Maki is a 12-year-old only child who was diagnosed with high functioning autism in Dec 2023. Hazel said he also received an autism diagnostic observation schedule test in February that was used to diagnose autism spectrum disorder by observing and evaluating social and communication behaviors.

But Hazel said she was suspicious of Maki’s behavior when he was a baby.

“I remember I said to his pediatrician,” Hazel said. “He was a baby and I was like, ‘Do you think you know it’s possible? He could be autistic?’”

Hazel said she remembered her son’s doctor denied her autistic claims because she claimed Maki as “focused” that caused her not to revisit the topic until recently when she learned what sensory issues were.

She said now that she knows more, she was frustrated with the school district and even herself for missing out on resources and direction for Maki while he was younger.

“I just had a feeling but I didn’t know I could have been in denial,” Hazel said. “I’m not going to say I wasn’t, but it was never brought to me like ‘You may want to have him tested or evaluated to see what it is.’”

Thriving today

Ten years later, Kaci is now 18 years old. Smith said Kaci graduated high school last year with a 4.1 GPA. She now majors in pre-law in a college in Ohio.

After Kaci’s diagnosis in 2014, Smith said she went through different plans to better her daughter’s educational experience, such as being introduced to individualized education programs, a customized plan for students with disabilities governed by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and 504 plans, that falls under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in federally funded programs. And after finally finding something that worked for her, Smith said that wasn’t enough. Considering that resources from the school for her daughter were free, she still thinks back on the difficulties and time it took to get where they are now.

“I think because I had to go toe-to-toe with the teacher who was accusing her of misbehaving and then coming to find out this was the situation, it was a little difficult in the beginning,” Smith said. “Because the teacher did not – I don’t think – that she wanted to accept that this was the case, even though I kind of knew that it was something other than her misbehaving.”

On top of the resources and accommodations from the school, Smith said she hired a private tutor for Kaci. And within a year’s time, she said Kaci went from making mostly C’s and B’s to straight A’s.

“Because it wasn’t that she didn’t have mental capacity, that wasn’t the issue,” Smith said. “The issue is that her processing speed is slower.”

Once Smith found the help she needed for Kaci, she said she became a strong advocate for her daughter and many others just like her.

Leave a comment