When the former police sergeant Maurice Hayes retired from the Durham Police Department (DPD) in 2008, he said the department met its target goal of responding to priority 1 calls.

Years later, Hayes, a Durham resident, moved out of the city because crime – and the response time by patrol officers – had both increased.

In the last 10 years, the DPD has only reached its target goal of patrol officers responding to priority one calls a total of five times. In this year’s first quarterly report, the DPD has hit its highest averaged response time of 6 minutes and 38 seconds – 50 seconds past its target goal of 5 minutes and 48 seconds.

Hayes said once he retired, he “didn’t want to be a civilian” while his wife was in the same environment.

His daughter lives within Durham’s Partners Against Crime (PAC) district four.

PAC districts are service districts in the city divided by the DPD. Durham has five (PAC) service districts. According to the department’s statistics, and opinions of patrol officers, district four has the largest population and the worst crime rate. The district’s borders range from Hillside Avenue/St. Teresa to the Parkwood Lake Playground, nearly nine miles apart.

When he realized his daughter planned to stay in Durham, Hayes demanded she learn how to use a gun and get a concealed carry license.

“I said I would never put a gun in my daughter’s hand,” Hayes said. “But I knew she would not see many police cars because the response would be slow. I knew that officers would be busy answering calls all over the city.”

Calls are ranked from nine to one priority. It’s a system measured on urgency where the lower the number, the higher the priority with the exception of “P,” according to the DPD. “P” is the most extreme ranked priority.

Former Durham City council member Jacqueline “Jackie” Wagstaff said the time matters.

“It’s about life or death. Simple as that,” she said. “A few minutes can be the factor of someone living or dying.”

Because of the slow response, many citizens would rather attempt to save themselves than rely on the police, Wagstaff said.

“That’s what you hear a lot about. People are taking victims and just putting them in the car and rushing them to the hospital,” Wagstaff said. “They can’t afford to wait for a response from that 911 call because most of the time, you’re not getting through.”

A dual challenge of population and staffing

Over the last few years, Durham has undergone several operations and staff changes. City of Durham Council Member DeDreana Freeman said gentrification tied with a decline in police staffing is one of the reasons for increasing response times.

“There’s been an increase in population and an influx of housing that’s creating more urban sprawl all around. And then there’s having to police that – that takes a lot more officers,” she said.

Freeman is the Ward One Council Member of the City of Durham. Durham has three wards that lay on top of each PAC district. Freeman’s ward roughly covers the majority of PAC district, two, five and a small section of four.

Durham is the fourth largest city in the state. The 2023 population stands at 287,794 citizens. According to the DPD’s 2023 second quarterly report, the department currently has 418 sworn-in officers – 77% of its targeted capacity of 540 sworn-in officers.

418 sworn-in officers is also the lowest staffing level in the DPD since 2013.

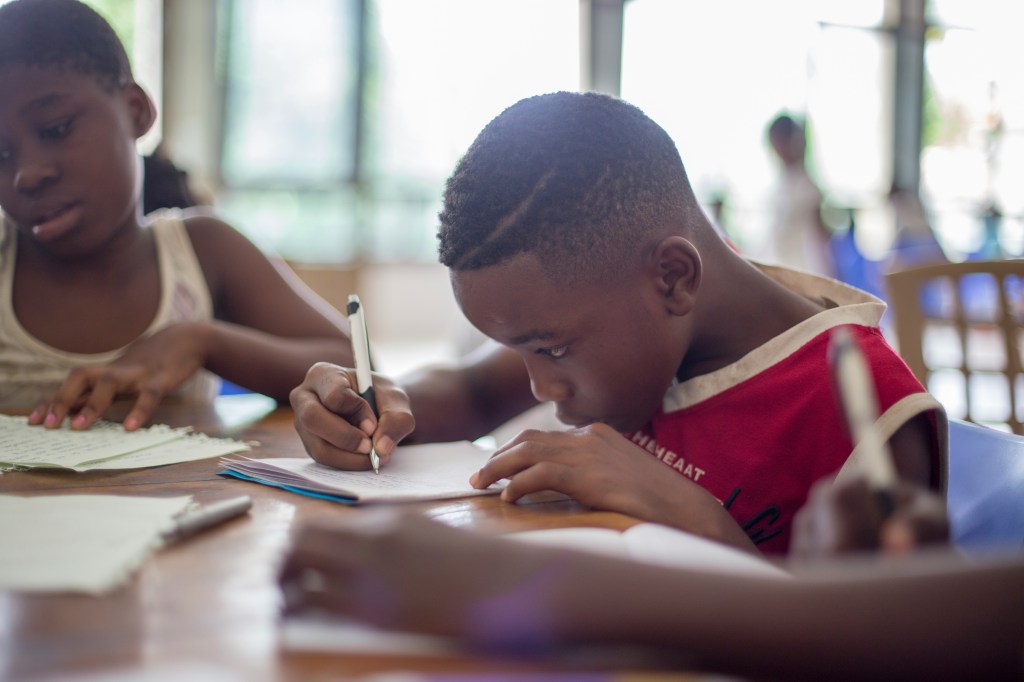

Durham’s PAC districts hold a total of 316 patrol officers. Depending on each 12-hour shift, patrol officers are required to work along with the number of officers of the same shift, that’s approximately 689 citizens to one officer.

Patrol officers from PAC districts two and four, said usual shifts consist of officers per district due to staff shortages. On average, a district two patrol officer said they receive about 15 calls per person per shift.

“Unfortunately, calls could be on hold for hours and that just depends on the call volume,” the officer said.

While each officer usually takes care of their own assigned calls, help from other officers is sometimes needed depending on population and crime rate, a district four officer said. With even two patrol officers on the same call, that district’s number of available officers goes down by 50% until that call is completed.

Covering the shortfall of staffing, investigators have started doing patrol work as well “because you have to have coverage on the streets,” Council Member Freeman said.

The DPD’s 2023 second quarterly property crime report stated that burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft have all been on the rise since last year.

“Those reports are ticking up and speaking more to those in poverty than to those who are not,” Freeman said.

She said the crime rates are a factor of inflation.

“With the increase of inflation, you know, if I can’t afford milk, bread, or gas for my car, I’m gonna figure out how to afford it. People don’t just say I’m going to starve,” Freeman said. “So they find new ways to get money or different ways to take care of their families. Add that in with a lack of police presence…the shortage is creating a dual harm not just to the community, but to the officers themselves.”

“Recipe for danger”

Former Council Member Jackie Wagstaff believes part of the problem of increasing response times stem from specific elected city officials business plans and the “Defund the Police” movement, which caused city officials to reallocate money from the DPD to other programs.

In the City of Durham council meetings, motions and votes to reallocate finances from the DPD’s budget have been made to put into other programs such as the Community Safety Task Force and the HEART program.

Wagstaff said the movement continued with efforts from former Mayor Pro-Tempore Jillian Johnson.

“She was the spearhead person for the ‘Defund the Police’ [thing]. She spent her whole entire career on that council promoting ‘Defund the Police,’” Wagstaff said. “Every year when it was time for that budget to be passed. She was adamant about not increasing the funding for the police department on no levels.”

The “Defund the Police” movement, sparked nationally in 2020 after George Floyd’s death, aims to redirect funds from police departments to non-policing services, reducing reliance on deadly force.

Wagstaff said that Johnson used this national movement during the beginning of her tenure and found new ways to “defund the police” after the “George Floyd phenomena died down.”

“She started proposing programs that can take money from the police department and reallocated it to other things that she felt could defund the police without saying it like the HEART team,” Wagstaff said. “That’s her baby.”

The Durham Voice reached out to Johnson to comment. However, Johnson said in an email she “did not have time to sit for an interview before my departure on Dec. 4” because she was “in my last few weeks on city council.”

Cisco Sales Leader, member of the City of Durham Workforce Development Board and member of the Preservation Durham Board Marshall Williams Jr., who ran for mayor in 2023, said this “political change” of defunding the police is a “direct reflection” to the increasing response times and officers’ pay.

“Our police need to be supported with more resources. I don’t think we have done enough as a city to actually honor our first responders and police officers to make it better for them to not go somewhere else,” Williams said. “We’ve got one of the highest crime rates and one of the least funded police departments, that’s a recipe for more danger.”

Freeman said she opposes the movement as well.

“Folks in the city have pushed to just shut down the police department, or to take money out of the police department and put it into other areas without the community being behind it,” Freeman said. “Of course, everyone isn’t on board with having police officers kill children or kill people. But with a very theoretical mindset that says ‘if you take the money out of the equation, that’ll be in part of the demilitarization and decriminalization of a city.’ And that hasn’t happened.”

She also said the movement has “created a low morale for the department.”

“Not paying officers for the work that they do and not giving them the tools they need to do the work is just not a good way to move forward,” Freeman said. “A lot of officers have left or retired. Even our police chief does not feel supported.”

Hiring incentives

Most city employees struggle to afford living in Durham due to low pay, including DPD officers. Durham’s average cost of living is $36,136 per person. The base salary of a certified patrol officer in Durham is $47,938 without taxes.

“We’re obviously hiring people. But we do need more money to attract more applicants. That’s been a struggle for us,” said Recruiting officer Nicholas Parkstone. “We’re one of the lowest paid in the state. So paying us for the job we do at an appropriate rate is so we can live in the city we work for. That would be a good first step.”

At a police recruiting open house, Recruiting officer Ryan Harris shared that the department is offering up to $13,000 in hiring incentives, but it’s not enough to live in Durham.

These come from relocations, “successful completion of the BLET and the remaining $5,000 after the successful completion of the PTO program,” said the DPD Media staff in an email.

The media team also said that they provide “daily” hiring advertisements on “DATA (GoDurham) buses, billboards, radio ads to name a few.”

Apart from the department, Wagstaff said the focus should start from the top as a way to solve the increased time.

She said current city leadership is “more citizen oriented rather than business oriented,” and plays a role in police retention due to housing plans.

“We have a problem with retention. We have a [bigger] problem with even having enough people out here to do the job that is needed if [elected city officials] are going to keep approving as much development as they approve,” Wagstaff said. “That means that’s more people. And when you have more people, that’s more problem.”

Leave a comment